Assisted hatching improves implantation in the uterine lining to increase the chance of a successful pregnancy

Assisted hatching is used in almost all in vitro fertilization cycles to increase implantation rates and the chances of conception. Research suggests that a certain number of otherwise viable embryos do not implant simply because they are unable to break free from the surrounding “jelly coat” (called the zona pellucida) when they reach the blastocyst stage of development. Allowing the embryo to “hatch” from its protective coating can help it make contact with the lining of the uterus and implant.

Assisted hatching is used in almost all in vitro fertilization cycles to increase implantation rates and the chances of conception. Research suggests that a certain number of otherwise viable embryos do not implant simply because they are unable to break free from the surrounding “jelly coat” (called the zona pellucida) when they reach the blastocyst stage of development. Allowing the embryo to “hatch” from its protective coating can help it make contact with the lining of the uterus and implant.

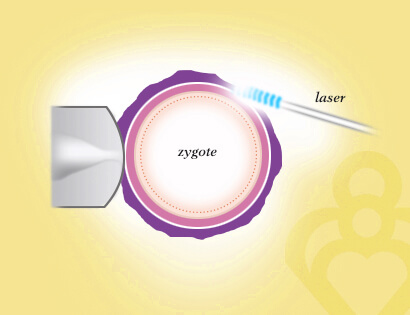

Around an unfertilized egg there exists a transparent glyco-protein coat that acts to protect the egg and regulate normal fertilization by any penetrating sperm. This jelly-like coat continues to protect the early preimplantation embryo until, as a blastocyst, the embryo fills itself up with fluid like a water-filled balloon, pumping itself larger and larger until it ruptures and “hatches” from the zona pellucida. The embryo is now ready to make contact in its naked form with the endometrium and implant.

An inhospitable ovarian environment due to advanced maternal age or other factors that may compromise the follicular environment may in certain cases render the zona pellucida thicker or tougher. Such IVF cases may benefit from the application of assisted hatching. In this process, a laser is used to weaken a specific area of the zona pellucida allowing the blastocyst to “hatch” free as it expands in the uterus.

Assisted hatching was initially done with chemicals but is now more safely done with a laser. Initial studies indicated that only certain groups would benefit from this technique. With the advent of more routine transfer of blastocysts on day 5 or 6, it has become commonplace to use assisted hatching on all embryos that will be transferred as a blastocyst. The most common drawbacks to assisted hatching is a very slightly increased risk of identical twinning.